Art in the Elizabethan Era Portraits in a Frame in the Elizabethan Era

Portrait of Elizabeth I of England in her coronation robes. Copy c. 1600–1610 of a lost original of c. 1559.[1] The pose echoes the famous portrait of Richard Two in Westminster Abbey, the second known portrait of a British sovereign.

One of many portraits of its blazon, with a reversed Darnley confront design, c. 1585–xc, artist unknown

The portraiture of Elizabeth I spans the development of English royal portraits in the early mod menstruum (1400/1500-1800), depicting Queen Elizabeth I of England and Ireland (1533–1603), from the primeval representations of simple likenesses to the later complex imagery used to convey the power and aspirations of the land, every bit well as of the monarch at its head.

Fifty-fifty the earliest portraits of Elizabeth I contain symbolic objects such every bit roses and prayer books that would have carried meaning to viewers of her day. Later portraits of Elizabeth layer the iconography of empire—globes, crowns, swords and columns—and representations of virginity and purity, such as moons and pearls, with classical allusions, to present a circuitous "story" that conveyed to Elizabethan era viewers the majesty and significance of the 'Virgin Queen'.

Overview [edit]

Elizabeth "in blacke with a hoode and cornet", the Clopton Portrait, c. 1558–60

Portraiture in Tudor England [edit]

2 portraiture traditions had arisen in the Tudor courtroom since the days of Elizabeth'southward father, Henry 8. The portrait miniature developed from the illuminated manuscript tradition. These small-scale personal images were near invariably painted from life over the space of a few days in watercolours on vellum, stiffened past being glued to a playing card. Panel paintings in oils on prepared wood surfaces were based on preparatory drawings and were usually executed at life size, as were oil paintings on canvas.

Unlike her contemporaries in France, Elizabeth never granted rights to produce her portrait to a single artist, although Nicholas Hilliard was appointed her official limner, or miniaturist and goldsmith. George Gower, a fashionable court portraitist created Serjeant Painter in 1581, was responsible for blessing all portraits of the queen created by other artists from 1581 until his expiry in 1596.[two]

Elizabeth sat for a number of artists over the years, including Hilliard, Cornelis Ketel, Federico Zuccaro or Zuccari, Isaac Oliver, and well-nigh probable to Gower and Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger.[2] Portraits were commissioned past the government as gifts to foreign monarchs and to show to prospective suitors. Courtiers commissioned heavily symbolic paintings to demonstrate their devotion to the queen, and the fashionable long galleries of later Elizabethan state houses were filled with sets of portraits. The studios of Tudor artists produced images of Elizabeth working from canonical "confront patterns", or approved drawings of the queen, to meet this growing demand for her prototype, an important symbol of loyalty and reverence for the crown in times of turbulence.[2]

European context [edit]

A copy of Holbein's Whitehall Mural.

By far the nigh impressive models of portraiture available to English portraitists were the many portraits by Hans Holbein the Younger, the outstanding Northern portraitist of the first half of the 16th century, who had made two lengthy visits to England, and had been Henry Eight's court artist. Holbein had accustomed the English court to the full-length life-size portrait,[3] [a] although none of his originals now survive. His great dynastic landscape at Whitehall Palace, destroyed in 1698, and possibly other original big portraits, would have been familiar to Elizabethan artists.[b]

Both Holbein and his corking Italian contemporary Titian had combined peachy psychological penetration with a sufficiently royal impression to satisfy their royal patrons. By his 2nd visit, Holbein had already begun to move away from a strictly realist depiction; in his Jane Seymour, "the figure is no longer seen as displacing with its bulk a recognizable department of space: information technology approaches rather to a flat pattern, made alive by a bounding and vital outline".[4] This trend was to exist taken much further by the later portraits of Elizabeth, where "Likeness of feature and an interest in form and book take gradually been abandoned in favour of an consequence of fantabulous majesty obtained by decorative pattern, and the forms have been flattened accordingly".[5]

Mary I, Anthonis Mor, 1554

Eleanor of Toledo and her son Giovanni, Bronzino, 1545

Titian'south full-length portrait of Philip Ii

Titian continued to paint royal portraits, especially of Philip II of Spain, until the 1570s, but in sharply reduced numbers after about 1555, and he refused to travel from Venice to practise them.[vi] The total-length portrait of Philip (1550–51) now in the Prado was sent to Elizabeth's elderberry sister and predecessor Mary I in advance of their matrimony.[c]

Towards the mid-16th century, the almost influential Continental courts came to prefer less revealing and intimate works,[9] and at the mid-century the ii about prominent and influential royal portraitists in pigment, other than Titian, were the Netherlandish Anthonis Mor and Agnolo Bronzino in Florence, too whom the Habsburg court sculptor and medallist Leone Leoni was similarly skilled. Mor, who had risen quickly to prominence in 1540s, worked across Europe for the Habsburgs in a tighter and more rigid version of Titian'south compositional manner, drawing besides on the North Italian style of Moretto.[10] Mor had actually visited London in 1554, and painted three versions of his well-known portrait of Queen Mary; he also painted English courtiers who visited Antwerp.[11] [d]

Mor'southward Castilian student Alonso Sánchez Coello continued in a stiffer version of his master's style, replacing him as Spanish court painter in 1561. Sofonisba Anguissola had painted in an intimately breezy style, simply afterwards her recruitment to the Castilian courtroom as the Queen's painter in 1560 was able to adapt her mode to the much more formal demands of state portraiture. Moretto'southward educatee Giovanni Battista Moroni was Mor's contemporary and formed his mature manner in the 1550s, but few of his spirited portraits were of royalty, or yet to be seen exterior Italian republic.[e]

Bronzino developed a mode of coldly distant magnificence, based on the Mannerist portraits of Pontormo, working almost entirely for Cosimo I, the showtime Medici Grand-Knuckles.[f] Bronzino'south works, including his hit portraits of Cosimo's Duchess, Eleanor of Toledo were distributed in many versions across Europe, standing to be made for two decades from the same studio design; a new portrait painted in her concluding years, about 1560, exists in merely a few repetitions. At the least many of the foreign painters in London are likely to have seen versions of the earlier type, and in that location may well accept been one in the Majestic Drove.

French portraiture remained dominated past small but finely drawn bosom-length or half-length works, including many drawings, ofttimes with colour, by François Clouet following, with a host of imitators, his father Jean, or even smaller oils past the Netherlandish Corneille de Lyon and his followers, typically no taller than a paperback book. A few total-length portraits of royalty were produced, dependent on German or Italian models.[14]

Creating the majestic image [edit]

Elizabeth Tudor every bit a Princess, c. 1546, by an unknown artist.

William Gaunt contrasts the simplicity of the 1546 portrait of Elizabeth Tudor every bit a Princess with afterward images of her every bit queen. He wrote, "The painter...is unknown, but in a competently Flemish mode he depicts the daughter of Anne Boleyn as placidity and studious-looking, ornament in her attire as secondary to the plainness of line that emphasizes her youth. Not bad is the contrast with the awesome fantasy of the later on portraits: the pallid, mask-similar features, the extravagance of headdress and ruff, the padded ornateness that seemed to exclude all humanity."[15]

The lack of emphasis given to depicting depth and book in her later portraits may take been influenced by the Queen's ain views. In the Art of Limming, Hilliard cautioned confronting all but the minimal apply of chiaroscuro modelling seen in his works, reflecting the views of his patron: "seeing that best to prove oneself needeth no shadow of place only rather the open up lite...Her Majesty..chose her identify to sit down for that purpose in the open alley of a goodly garden, where no tree was nigh, nor any shadow at all..."[xvi]

From the 1570s, the government sought to manipulate the paradigm of the queen as an object of devotion and veneration. Sir Roy Potent writes: "The cult of Gloriana was skilfully created to buttress public order and, fifty-fifty more, deliberately to replace the pre-Reformation externals of organized religion, the cult of the Virgin and saints with their bellboy images, processions, ceremonies and secular rejoicing."[17] The pageantry of the Accession Day tilts, the poetry of the court, and the near iconic of Elizabeth's portraits all reflected this effort. The management of the queen's prototype reached its heights in the final decade of her reign, when realistic images of the aging queen were replaced with an eternally youthful vision, defying the reality of the passage of time.

Early on portraits [edit]

The young queen [edit]

Portraits of the young queen, many of them probable painted to be shown to prospective suitors and strange heads of state, show a naturality and restraint similar to that of the portrait of Elizabeth as a princess.

The Hampden Portrait of Elizabeth I, 1560s

The full-length Hampden epitome of Elizabeth in a red satin gown, originally attributed to Steven van der Meulen and reattributed to George Gower in 2020,[18] has been identified by Sir Roy Strong equally an of import early portrait, "undertaken at a fourth dimension when her image was beingness tightly controlled", and produced "in response to a crisis over the production of the royal paradigm, one which was reflected in the words of a draft proclamation dated 1563".[19] The draft proclamation (never published) was a response to the circulation of poorly-made portraits in which Elizabeth was shown "in blacke with a hoode and cornet", a style she no longer wore.[20] [chiliad] Symbolism in these pictures is in keeping with earlier Tudor portraiture; in some, Elizabeth holds a volume (perchance a prayer book) suggesting studiousness or piety. In other paintings, she holds or wears a red rose, symbol of the Tudor Dynasty's descent from the House of Lancaster, or white roses, symbols of the House of York and of maidenly chastity.[21] In the Hampden portrait, Elizabeth wears a red rose on her shoulder and holds a gillyflower in her hand. Of this paradigm, Strong says "Here Elizabeth is defenseless in that short-lived catamenia before what was a recognisable homo became transmuted into a goddess".[19] [h]

One artist active in Elizabeth'south early on court was the Flemish miniaturist Levina Teerlinc, who had served as a painter and gentlewoman to Mary I and stayed on as a Gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber to Elizabeth. Teerlinc is best known for her pivotal position in the rise of the portrait miniature. There is documentation that she created numerous portraits of Elizabeth I, both individual portraits and portraits of the sovereign with important courtroom figures, simply just a few of these have survived and been identified.[23]

Elizabeth and the goddesses [edit]

Elizabeth I and the Three Goddesses, 1569

2 surviving allegorical paintings show the early use of classical mythology to illustrate the beauty and sovereignty of the immature queen. In Elizabeth I and the Three Goddesses (1569), attributed to Hans Eworth,[i] the story of the Judgement of Paris is turned on its head. Elizabeth, rather than Paris, is at present sent to cull among Juno, Venus, and Pallas-Minerva, all of whom are outshone by the queen with her crown and imperial orb. As Susan Doran writes, "Implicit to the theme of the painting ... is the idea that Elizabeth's retention of majestic ability benefits her realm. Whereas Paris's sentence in the original myth resulted in the long Trojan Wars 'to the utter ruin of the Trojans', hers will conversely bring peace and order to the state"[26] after the turbulent reign of Elizabeth's sister Mary I.

The latter theme lies behind the 1572 The Family of Henry 8: An Apologue of the Tudor Succession (attributed to Lucas de Heere). In this paradigm, Catholic Mary and her husband Philip II of Kingdom of spain are accompanied by Mars, the god of War, on the left, while Protestant Elizabeth on the right ushers in the goddesses Peace and Plenty.[27] An inscription states that this painting was a souvenir from the queen to Francis Walsingham as a "Mark of her people's and her own content", and this may indicate that the painting commemorates the signing of the Treaty of Blois (1572), which established an alliance between England and France against Spanish assailment in the netherlands during Walsingham's tour of duty as ambassador to the French court.[28] Strong identifies both paintings equally celebrations of Elizabeth'southward just rule by Flemish exiles, to whom England was a refuge from the religious persecution of Protestants in the Spanish Netherlands.[25]

Hilliard and the queen [edit]

Miniature by Hilliard, 1572

The Phoenix Portrait, c. 1575, attributed to Hilliard

Emmanuel College charter, 1584

Nicholas Hilliard was an amateur to the Queen's jeweller Robert Brandon,[29] a goldsmith and city chamberlain of London, and Strong suggests that Hilliard may also accept been trained in the art of limning by Levina Teerlinc.[29] Hilliard emerged from his apprenticeship at a time when a new royal portrait painter was "desperately needed."[29]

Hilliard'southward beginning known miniature of the Queen is dated 1572. It is not known when he was formally appointed limner (miniaturist) and goldsmith to Elizabeth,[30] though he was granted the reversion of a lease past the Queen in 1573 for his "good, true and loyal service."[31] 2 panel portraits long attributed to him, the Phoenix and Pelican portraits, are dated c. 1572–76. These paintings are named later on the jewels the queen wears, her personal badges of the pelican in her piety and the phoenix. National Portrait Gallery researchers announced in September 2010 that the two portraits were painted on wood from the same 2 copse; they also institute that a tracing of the Phoenix portrait matches the Pelican portrait in contrary, deducing that both pictures of Elizabeth in her forties were painted around the same time.[32]

Yet, Hilliard'due south panel portraits seem to have been found wanting at the fourth dimension, and in 1576 the recently married Hilliard left for French republic to improve his skills. Returning to England, he continued to piece of work as a goldsmith, and produced some spectacular "picture boxes" or jewelled lockets for miniatures: the Armada Precious stone, given by Elizabeth to Sir Thomas Heneage and the Drake Pendant given to Sir Francis Drake are the best known examples. As part of the cult of the Virgin Queen, courtiers were expected to wear the Queen'south likeness, at to the lowest degree at Courtroom.

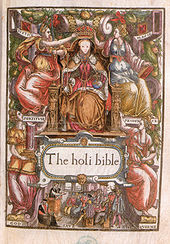

Hilliard's appointment as miniaturist to the Crown included the old sense of a painter of illuminated manuscripts and he was commissioned to decorate important documents, such as the founding charter of Emmanuel College, Cambridge (1584), which has an enthroned Elizabeth nether a canopy of estate within an elaborate framework of Flemish-style Renaissance strapwork and grotesque ornament. He also seems to have designed woodcut title-page frames and borders for books, some of which carry his initials.[33]

The Darnley Portrait [edit]

The Darnley Portrait, c. 1575

The problem of an official portrait of Elizabeth was solved with the Darnley Portrait.[j] Likely painted from life around 1575–6, this portrait is the source of a face pattern which would exist used and reused for authorized portraits of Elizabeth into the 1590s, preserving the impression of ageless beauty. Potent suggests that the artist is Federico Zuccari or Zucaro, an "eminent" Italian creative person, though non a specialist portrait-painter, who is known to have visited the court briefly with a letter of introduction to Elizabeth'southward favourite Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, dated 5 March 1575.[35] Zuccaro'southward preparatory drawings for full-length portraits of both Leicester and Elizabeth survive, although information technology is unlikely the total-length of Elizabeth was ever painted.[35] Curators at the National Portrait Gallery believe that the attribution of the Darnley portrait to Zuccaro is "not sustainable", and aspect the work to an unknown "continental" (perhaps Netherlandish) artist.[36]

The Darnley Portrait features a crown and sceptre on a table beside the queen, and was the starting time advent of these symbols of sovereignty separately used as props (rather than worn and carried) in Tudor portraiture, a theme that would exist expanded in later portraits.[35] Recent conservation piece of work has revealed that Elizabeth's now-iconic pale complexion in this portrait is the event of deterioration of red lake pigments, which has likewise contradistinct the coloring of her wearing apparel.[37] [38]

The Virgin Empress of the Seas [edit]

Return of the Gold Age [edit]

The Ermine Portrait, variously attributed to William Segar or George Gower, 1585.[18] Elizabeth as Pax (lit., "peace").

The excommunication of Elizabeth past Pope Pius V in 1570 led to increased tension with Philip Ii of Spain, who championed the Cosmic Mary, Queen of Scots, as the legitimate heir of his belatedly wife Mary I. This tension played out over the adjacent decades in the seas of the New Earth too every bit in Europe, and culminated in the invasion effort of the Spanish Armada.

It is confronting this backdrop that the beginning of a long series of portraits appears, depicting Elizabeth with heavy symbolic overlays of the possession of an empire based on mastery of the seas.[39] Combined with a second layer of symbolism representing Elizabeth equally the Virgin Queen, these new paintings signify the manipulation of Elizabeth's image equally the destined Protestant protector of her people.[ commendation needed ]

Stiff points out that at that place is no trace of this iconography in portraits of Elizabeth prior to 1579, and identifies its source as the witting image-making of John Dee, whose 1577 General and Rare Memorials Pertayning to the Perfect Arte of Navigation encouraged the establishment of English colonies in the New World supported by a stiff navy, asserting Elizabeth'south claims to an empire via her supposed descent from Brutus of Troy and King Arthur.[40]

Dee's inspiration lies in Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, which was accepted as truthful history past Elizabethan poets,[ citation needed ] and formed the basis of the symbolic history of England. In this twelfth-century pseudohistory, Great britain was founded by and named after Brutus, the descendant of Aeneas, who founded Rome. The Tudors, of Welsh descent, were heirs of the about aboriginal Britons and thus of Aeneas and Brutus. By uniting the Houses of York and Lancaster following the strife of the Wars of the Roses, the Tudors ushered in a united realm where Pax - Latin for "peace", and the Roman goddess of peace - reigned.[41] The Spenserian scholar Edwin Greenlaw states "The descent of the Britons from the Trojans, the linking of Arthur, Henry Viii, and Elizabeth as U.k.'s greatest monarchs, and the return under Elizabeth of the Golden Age are all commonplaces of Elizabethan idea."[42] This understanding of history and Elizabeth'southward place in it forms the background to the symbolic portraits of the latter half of her reign.

The Virgin Queen [edit]

A serial of Sieve Portraits copied the Darnley face up design, and added an allegorical overlay that depicted Elizabeth as Tuccia, a Vestal Virgin who proved her chastity by conveying a sieve full of h2o from the Tiber River to the Temple of Vesta without spilling a drop.[43] The beginning Sieve Portrait was painted by George Gower in 1579, simply the near influential image is the 1583 version by Quentin Metsys (or Massys) the Younger.[g]

In the Metsys version, Elizabeth is surrounded past symbols of empire, including a column and a earth, iconography that would announced once again and over again in her portraiture of the 1580s and 1590s, most notably in the Armada Portrait of c. 1588.[45] The medallions on the colonnade to the left of the queen illustrate the story of Dido and Aeneas, antecedent of Brutus, suggesting that like Aeneas, Elizabeth's destiny was to reject matrimony and establish an empire. This painting'due south patron was likely Sir Christopher Hatton, as his heraldic badge of the white hind appears on the sleeve of i of the courtiers in the background, and the work may have expressed opposition to the proposed marriage of Elizabeth to François, Duke of Anjou.[46] [47]

The virgin Tuccia was familiar to Elizabethan readers from Petrarch'southward "The Triumph of Guiltlessness". Another symbol from this work is the spotless ermine, wearing a collar of gold studded with topazes.[48] This symbol of purity appears in the Ermine Portrait of 1585, attributed to the herald William Segar. The queen bears the olive branch of Pax (Peace), and the sword of justice rests on the table at her side.[49] In combination, these symbols represent not only the personal purity of Elizabeth just the "righteousness and justice of her government."[fifty]

Visions of empire [edit]

The Woburn Abbey version of the Armada Portrait, c. 1588

The Fleet Portrait is an allegorical console painting depicting the queen surrounded by symbols of empire confronting a properties representing the defeat of the Castilian Armada in 1588.

There are three surviving versions of the portrait, in addition to several derivative paintings. The version at Woburn Abbey, the seat of the Dukes of Bedford, was long accepted as the piece of work of George Gower, who had been appointed Serjeant Painter in 1581.[51] A version in the National Portrait Gallery, London, which had been cut down at both sides leaving merely a portrait of the queen, was as well formerly attributed to Gower. A 3rd version, owned by the Tyrwhitt-Drake family, may have been commissioned by Sir Francis Drake. Scholars agree that this version is past a unlike hand, noting distinctive techniques and approaches to the modelling of the queen'due south features.[51] [52] [l] Curators now believe that the three extant versions are all the output of different workshops under the management of unknown English artists.[54]

The combination of a life-sized portrait of the queen with a horizontal format is "quite unprecedented in her portraiture",[51] although emblematic portraits in a horizontal format, such every bit Elizabeth I and the Three Goddesses and the Family of Henry Viii: An Allegory of the Tudor Succession pre-date the Armada Portrait.

Engraving by Crispijn van de Passe, printed 1596

The queen's hand rests on a globe below the crown of England, "her fingers covering the Americas, indicating England'south [command of the seas] and [dreams of establishing colonies] in the New World".[55] [56] The Queen is flanked by 2 columns behind, probably a reference to the famous impresa of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles 5, Philip II of Espana's father, which represented the pillars of Hercules, gateway to the Atlantic Body of water and the New World.[57]

In the background view on the left, English language fireships threaten the Spanish fleet, and on the right the ships are driven onto a rocky coast amid stormy seas by the "Protestant Current of air". On a secondary level, these images show Elizabeth turning her back on tempest and darkness while sunlight shines where she gazes.[51]

An engraving by Crispijn van de Passe (Crispin van de Passe) published in 1596, but showing costume of the 1580s, carries similar iconography. Elizabeth stands between 2 columns bearing her artillery and the Tudor heraldic bluecoat of a portcullis. The columns are surmounted by her emblems of a pelican in her piety and a phoenix, and ships fill the sea backside her.[58]

The cult of Elizabeth [edit]

The diverse threads of mythology and symbolism that created the iconography of Elizabeth I combined into a tapestry of immense complexity in the years following the defeat of the Spanish Fleet. In poetry, portraiture and pageantry, the queen was celebrated as Astraea, the just virgin, and simultaneously as Venus, the goddess of dear. Another exaltation of the queen's virgin purity identified her with the moon goddess, who held dominion over the waters. Sir Walter Raleigh had begun to employ Diana, and afterwards Cynthia, as aliases for the queen in his poetry around 1580, and images of Elizabeth with jewels in the shape of crescent moons or the huntress's arrows begin to appear in portraiture around 1586 and multiply through the remainder of the reign.[59] Courtiers wore the image of the Queen to signify their devotion, and had their portraits painted wearing her colours of black and white.[60]

The Ditchley Portrait seems to accept always been at the Oxfordshire home of Elizabeth'due south retired Champion, Sir Henry Lee of Ditchley, and likely was painted for (or commemorates) her ii-day visit to Ditchley in 1592. The painting is attributed to Marcus Gheerearts the Younger, and was well-nigh certainly based on a sitting bundled by Lee, who was the painter's patron. In this image, the queen stands on a map of England, her feet on Oxfordshire. The painting has been trimmed and the background poorly repainted, and then that the inscription and sonnet are incomplete. Storms rage behind her while the lord's day shines before her, and she wears a jewel in the form of a celestial or armillary sphere close to her left ear. Many versions of this painting were made, likely in Gheeraerts' workshop, with the allegorical items removed and Elizabeth's features "softened" from the stark realism of her face in the original. I of these was sent as a diplomatic gift to the Thousand Duke of Tuscany, and is now in the Palazzo Pitti.[61]

The last sitting and the Mask of Youth [edit]

The unfinished miniature by Isaac Oliver, c. 1592

Recently discovered miniature by Hilliard, 1595–1600

Around 1592, the queen also sabbatum to Isaac Oliver, a student of Hilliard, who produced an unfinished portrait miniature used as a pattern for engravings of the queen. Simply a single finished miniature from this design survives, with the queen's features softened, and Strong concludes that this realistic image from life of the aging Elizabeth was not deemed a success.[62]

Prior to the 1590s, woodcuts and engravings of the queen were created every bit book illustrations, but in this decade individual prints of the queen first announced, based on the Oliver face pattern. In 1596, the Privy Council ordered that unseemly portraits of the queen which had caused her "great offence" should be sought out and burnt, and Strong suggest that these prints, of which comparatively few survive, may be the offending images. Strong writes "It must take been exposure to the searching realism of both Gheeraerts and Oliver that provoked the decision to suppress all likenesses of the queen that depicted her as being in any way quondam and hence subject field to bloodshed."[63]

In any effect, no surviving portraits dated between 1596 and Elizabeth'south expiry in 1603 prove the aging queen as she truly was. Faithful resemblance to the original is only to be found in the accounts of contemporaries, equally in the written report written in 1597 by André Hurault de Maisse, Ambassador Boggling from Henry IV of France, after an audience with the sixty-five yr-old queen, during which he noted, "her teeth are very xanthous and unequal ... and on the left side less than on the correct. Many of them are missing, so that one cannot understand her easily when she speaks rapidly." Yet he added, "her figure is fair and tall and svelte in any she does; so far every bit may exist she keeps her dignity, withal humbly and graciously yet."[64] All subsequent images rely on a face design devised past Nicholas Hilliard old in the 1590s called by art historians the "Mask of Youth", portraying Elizabeth as always-young.[63] [65] Some sixteen miniatures by Hilliard and his studio are known based on this face up pattern, with unlike combinations of costume and jewels likely painted from life, and it was also adopted by (or enforced on) other artists associated with the Court.[63]

The coronation portraits [edit]

Ii portraits of Elizabeth in her coronation robes survive, both dated to 1600 or presently thereafter. I is a panel portrait in oils, and the other is a miniature by Nicholas Hilliard.[66] The warrant to the queen's tailor for remodelling Mary I'south cloth of gold coronation robes for Elizabeth survives, and costume historian Janet Arnold's report points out that the paintings accurately reflect the written records, although the jewels differ in the two paintings,[i] suggesting two dissimilar sources, i possibly a miniature by Levina Teerlinc. It is not known why, and for whom, these portraits were created, at, or only after, the cease of her reign.[67]

The Rainbow Portrait [edit]

The Rainbow Portrait, c. 1600–02, attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger

Attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger,[68] perhaps the most heavily symbolic portrait of the queen is the Rainbow Portrait at Hatfield Business firm. It was painted effectually 1600–1602, when the queen was in her sixties. In this painting, an ageless Elizabeth appears dressed every bit if for a masque, in a linen bodice embroidered with spring flowers and a mantle draped over 1 shoulder, her hair loose beneath a fantastical headdress.[69] She wears symbols out of the pop emblem books, including the cloak with eyes and ears, the serpent of wisdom, and the celestial armillary sphere, and carries a rainbow with the motto non sine sole iris ("no rainbow without the sun"). Strong suggests that the complex "program" for this image may be the piece of work of the poet John Davies, whose Hymns to Astraea honouring the queen use much of the same imagery, and suggests it was commissioned past Robert Cecil equally role of the decor for Elizabeth's visit in 1602, when a "shrine to Astraea" featured in the entertainments of what would prove to be the "last smashing festival of the reign".[69] [70]

Books and coins [edit]

Prior to the wide dissemination of prints of the queen in the 1590s, the common people of Elizabeth'south England would be most familiar with her image on the coinage. In December 1560, a systematic recoinage of the debased money then in circulation was begun. The main early on endeavour was the issuance of sterling silver shillings and groats, only new coins were issued in both silver and gold. This restoration of the currency was one of the iii main achievements noted on Elizabeth's tomb, illustrating the value of stable currency to her contemporaries.[71] Later coinage represented the queen in iconic fashion, with the traditional accompaniments of Tudor heraldic badges including the Tudor rose and portcullis.

Books provided another widely bachelor source of images of Elizabeth. Her portrait appeared on the title page of the Bishops' Bible, the standard Bible of the Church of England, issued in 1568 and revised in 1572. In various editions, Elizabeth is depicted with her orb and sceptre accompanied by female person personifications.[72]

"Reading" the portraits [edit]

Portrait in the Palazzo Pitti, Florence

The many portraits of Elizabeth I establish a tradition of prototype highly steeped in classical mythology and the Renaissance understanding of English language history and destiny, filtered by allusions to Petrarch's sonnets and, late in her reign, to Edmund Spenser'south Faerie Queene. This mythology and symbology, though directly understood by Elizabethan contemporaries for its political and symbolic meaning, makes information technology hard to 'read' the portraits in the present day as contemporaries would accept seen them at the fourth dimension of their cosmos. Though knowledge of the symbology of Elizabethan portraits has not been lost, Dame Frances Yates points out that the most complexly symbolic portraits may all commemorate specific events, or have been designed as part of elaborately-themed entertainments, knowledge left unrecorded within the paintings themselves.[47] The most familiar images of Elizabeth—the Armada, Ditchley, and Rainbow portraits—are all associated with unique events in this style. To the extent that the contexts of other portraits take been lost to scholars, so too the keys to understanding these remarkable images as the Elizabethans understood them may be lost in fourth dimension; fifty-fifty those portraits that are not overtly allegorical may have been full of meaning to a discerning eye. Elizabethan courtiers familiar with the language of flowers and the Italian emblem books could have read stories in the flowers the queen carried, the embroidery on her clothes, and the pattern of her jewels.

According to Strong:

Fear of the wrong use and perception of the visual prototype dominates the Elizabethan age. The onetime pre-Reformation idea of images, religious ones, was that they partook of the essence of what they depicted. Any accelerate in technique which could reinforce that experience was embraced. That was at present reversed, indeed it may business relationship for the Elizabethans failing to accept cognisance of the optical advances which created the art of the Italian Renaissance. They certainly knew nigh these things but, and this is central to the understanding of the Elizabethans, chose non to employ them. Instead the visual arts retreated in favour of presenting a series of signs or symbols through which the viewer was meant to pass to an understanding of the idea behind the piece of work. In this style the visual arts were verbalised, turned into a form of book, a 'text' which called for reading by the onlooker. There are no ameliorate examples of this than the quite extraordinary portraits of the queen herself, which increasingly, as the reign progressed, took on the class of collections of abstruse design and symbols tending in an unnaturalistic fashion for the viewer to unravel, and by doing so enter into an inner vision of the idea of monarchy.[73]

Gallery [edit]

Queen and court [edit]

-

Unknown artist, The Family of Henry VIII, with Elizabeth on the right, c. 1545

-

Elizabeth and the Ambassadors, attributed to Levina Teerlinc, c. 1560

-

An Elizabethan Maundy, miniature by Teerlinc, c. 1560

-

The Family unit of Henry Eight, an Allegory of the Tudor Succession, 1572, attributed to Lucas de Heere

Portrait miniatures [edit]

-

Teerlinc, c. 1565

-

Hilliard, c. 1580

-

Hilliard, c. 1587

-

Hilliard, c. 1590

-

Hilliard, 1595–1600

Portraits [edit]

-

Unknown creative person, c. 1559

-

c. 1560

-

Unknown artist, 1560–65

-

The Gripsholm Portrait, 1563

-

-

Unknown creative person, 1570s

-

Nicholas Hilliard, c. 1576-78

-

The Schloss Ambras Portrait, unknown creative person, 1575–eighty

-

The Drewe Portrait, 1580s, George Gower

-

In Parliament Robes, 1585–90, attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger

-

Variant of the Armada Portrait, c. 1588

-

Portrait past an unknown artist, c. 1595

-

The Hardwick Hall Portrait, the Mask of Youth, Hilliard workshop, c. 1599

Portrait medallions and cameos [edit]

-

Portrait medallion, c. 1572–73, diplomatic souvenir to Adriaen de Manmaker, appointed Treasurer General of the province of Zeeland on twenty Oct 1573.[74]

-

Sir Francis Drake wearing the Drake Pendant, a cameo of the queen. Gheeraerts the Younger, 1591

Drawings [edit]

-

Preliminary chalk sketch for a portrait of Elizabeth I, Zuccaro, c. 1575

-

Design for the obverse of a Smashing Seal for Republic of ireland (never made), pen and ink wash over pencil, Hilliard, c. 1584

-

Pen and ink drawing on vellum by Isaac Oliver, c. 1592–95

Prints and coins [edit]

-

Coloured frontispiece to Christopher Saxton'south Atlas of England and Wales, 1579

-

Coloured engraving, Coram Rege ringlet, 1581

-

Engraving based on the Oliver design of c. 1592

-

Elizabeth equally Rosa Electa, Rogers, 1590–95

-

Engraving c. 1592–95 by Crispijn de Passe from the drawing by Oliver, with later inscription

-

Irish gaelic groat of 1561. Coins were of course the primary way the mass of her people received images of Elizabeth.

-

Gilded half-pound of 1560–61

Illuminated manuscripts [edit]

-

Illuminated initial membrane, Courtroom of Male monarch's Demote: Coram Rege Roll, Easter Term, 1572

-

Coram Rege Roll, Easter Term, 1584

-

Charter of Queen Elizabeth'southward Grammer School, Ashbourne, Hilliard, 1585

-

Coram Rege Ringlet, Easter Term, 1589

See also [edit]

- 1550–1600 in style

- Artists of the Tudor Court

- Cultural depictions of Elizabeth I of England

Notes [edit]

- ^ This was in notable contrast to France, in item, where smaller portraits remained more than typical until Henry Iv of France came to power in 1594.

- ^ Waterhouse (19–22) points out that only very high ranking persons could enter the room where the landscape was displayed when the court was in residence at Whitehall. Merely artists could probably accept gained access during the long periods when the monarch was elsewhere; certainly in that location are many credible copies of the figure of Henry from this piece of work.

- ^ The portrait came from Philip's aunt Mary in Brussels, presumably every bit a loan.[seven] It was presumably returned by or subsequently Mary I'due south death in 1558, as information technology is in a Spanish royal inventory of 1600.[eight] The painting returned to London for an exhibition at the National Gallery until Jan 2009.

- ^ Surviving portraits include those of Sir Thomas Gresham and Sir Henry Lee, who was later to commission the Ditchley Portrait.

- ^ Even in Italy, his best portraits were routinely attributed to Titian or Moretto; for example, what has always been his nigh famous work, the and so-called Titian'due south Schoolmaster, now resides in Washington, but was previously displayed in the Palazzo Borghese in Rome.[12]

- ^ In an extended give-and-take, Michael Levey says Bronzino showed the ducal family "so wrought and congealed that there is cipher of living tissue left in them. Their easily have turned to ivory, and their eyes to pieces of beautifully cutting, faceted jet."[13]

- ^ In these portraits Elizabeth may be wearing mourning for her sister Mary; see commentary on a portrait (Paradigm) of Mary, Queen of Scots in a similar black gown and French hood with the cornet or bongrace pinned upwards at "Mary Queen of Scots (1542 - 1587) c. 1558". Historical Portraits Image Library. Archived from the original on 16 Oct 2008. Retrieved 8 Nov 2008. , where the costume is compared to Elizabeth's in the Clopton portrait type.

- ^ This portrait was sold at Sotheby's, London, for £two.6 million in November 2007.[22]

- ^ The portrait is signed "H.Due east." and the artist formerly identified as the "Monogrammist H.E." is now generally causeless to be Hans Eworth.[24] Stiff had earlier attributed the painting to Joris Hoefnagel.[25]

- ^ Then-chosen from its location at Cobham House, much afterwards the seat of the Earls of Darnley.[34]

- ^ Although Strong attributed the painting to Cornelis Ketel in 1969 and once again in 1987,[44] closer exam has revealed that the painting is signed and dated on the base of operations of the globe 1583. Q. MASSYS

- ^ This version was heavily overpainted in the afterwards 17th century, which complicates attribution and may account for several differences in details of the costume.[53]

References [edit]

- ^ a b Arnold 1978

- ^ a b c Strong 1987, pp. 14–15

- ^ Waterhouse (1978), pp. 25–6.

- ^ Waterhouse:19

- ^ Waterhouse, p. 36

- ^ Fletcher, Jennifer in: David Jaffé (ed), Titian, pp. 31–2, The National Gallery Company/Yale, London 2003, ISBN one-85709-903-6

- ^ Fletcher, op. cit. pp. 31 and 148

- ^ Prado:398–99 (#411)

- ^ For analysis of this trend run into Levey (1971), Ch. three, and Trevor-Roper (1976) Ch. 1 and 2.

- ^ Waterhouse (1978), pp. 27–viii. For his relationship with the Habsburgs, come across Trevor-Roper (1976) passim, who too covers those of Leone Leoni and Titian in detail.

- ^ Waterhouse (1978), p. 28.

- ^ Penny:194–5 on his life and style, 196–seven on his reputation. Freedberg (1993), pp. 593–5 analyses his portrait manner.

- ^ Levey (1971), pp. 96–108 — quotation from p. 108. Come across also Freedberg (1993), pp. 430–35

- ^ Blunt, pp. 62–64

- ^ Gaunt, 37.

- ^ Quotation from Hilliard's Fine art of Limming, c. 1600, in Nicholas Hilliard, Roy Strong, 1975, p.24, Michael Joseph Ltd, London, ISBN 0-7181-1301-2

- ^ Strong 1977, p. 16

- ^ a b Town, Edward; David, Jessica (ane September 2020). "George Gower: portraitist, Mercer, Serjeant Painter". The Burlington Magazine. 162 (1410): 731–747.

- ^ a b "Portrait of a royal quest for a husband". The Independent, (London), Nov 1, 2007. Retrieved on 24 October 2008.

- ^ Strong 1987, p. 23

- ^ Doran 2003b, p. 177

- ^ Reuters news story

- ^ Strong 1987, pp. 55–57

- ^ Hearn 1995, p. 63

- ^ a b Stiff 1987, p. 42

- ^ Doran 2003b, p. 176

- ^ Hearn 1995, pp. 81–82

- ^ Doran 2003b, pp.185–86

- ^ a b c Stiff 1987, p. 79–83

- ^ Reynolds, Hilliard and Oliver, pp. 11–eighteen

- ^ Strong 1975, p.4

- ^ Pelican and Phoenix research

- ^ Potent, 1983, pp. 62 & 66

- ^ see Strong 1987 p. 86

- ^ a b c Potent 1987, p.85

- ^ Cooper and Bolland (2014), p. 147

- ^ Cooper and Bolland (2014), pp. 162-167

- ^ National Portrait Gallery (2014). "Making Art in Tudor United kingdom: 'Darnley' portrait". Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Strong 1987, pp. 91–93

- ^ Strong 1987, p. 91

- ^ Yates, pp. 50–51.

- ^ E[dwin] Greenlaw, Studies in Spenser's Historical Allegory, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Printing, 1932, quoted in Yates, p. 50.

- ^ See Hearn 1995, p. 85; Stiff 1987, p. 95

- ^ Strong 1987 p. 101

- ^ Hearn, p. 85; Strong 1987 p. 101

- ^ Doran 2003b, p. 187

- ^ a b Yates, p. 115

- ^ Yates pp. 115, 215–216

- ^ Strong 1987, p. 113

- ^ Yates, p. 216

- ^ a b c d Stiff 1987, Gloriana, p. 130–133

- ^ Hearn 1995 p. 88

- ^ Run across Arnold, Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlock'd, pp. 34–36

- ^ Cooper and Bolland (2014), pp. 151-154

- ^ Hearn 1995, p. 88

- ^ Andrew Belsey and Catherine Belsey, "Icons of Divinity: Portraits of Elizabeth I" in Gent and Llewellyen, Renaissance Bodies, pp. xi–35

- ^ Stiff 1984, p. 51

- ^ Strong 1987, p. 104

- ^ Potent 1987, pp. 125–127

- ^ Strong 1977, pp. lxx–75

- ^ Stiff 1987, pp. 135–37.

- ^ Strong 1987, p. 143

- ^ a b c Strong 1987, p. 147

- ^ De Maisse: a journal of all that was accomplished by Monsieur De Maisse, ambassador in England from Male monarch Henri IV to Queen Elizabeth, anno domini 1597, Nonesuch Printing, 1931, p. 25-26

- ^ Sotheby's Catalogue L07123, Important British Paintings 1500–1850, Nov 2007, p. 20

- ^ "Elizabeth I // Miniature Portraits // The Portland Collection".

- ^ Stiff 1987, pp. 162–63

- ^ Strong, Roy C. Gloriana: The Portraits of Queen Elizabeth I. Deutschland: Thames and Hudson, 1987. pg. 148

- ^ a b Strong 1987, pp. 157–160

- ^ Strong 1977, pp. 46–47

- ^ Doran 2003a, p. 52

- ^ Doran 2003a, p. 29

- ^ Strong (1999), p. 177

- ^ "A historical and important English/Dutch 20KT aureate-framed Elizabethan portrait miniature pendant, Christie's". Retrieved vi Apr 2012. . The Zeeuws Museum dates the medallion to 1572–73.

Bibliography [edit]

- Arnold, Janet: "The 'Coronation' Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I", The Burlington Mag, CXX, 1978, pp. 727–41.

- Arnold, Janet: Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlock'd, W S Maney and Son Ltd, Leeds 1988. ISBN 0-901286-20-6

- Blunt, Anthony, Fine art and Compages in France, 1500–1700, 2nd edn 1957, Penguin

- Cooper, Tarnya; Bolland, Charlotte (2014). The Real Tudors : kings and queens rediscovered. London: National Portrait Gallery. ISBN 9781855144927.

- Freedberg, Sidney J., Painting in Italy, 1500–1600, 3rd edn. 1993, Yale, ISBN 0-300-05587-0

- Gaunt, William: Courtroom Painting in England from Tudor to Victorian Times. London: Constable, 1980. ISBN 0-09-461870-4.

- Gent, Lucy, and Nigel Llewellyn, eds: Renaissance Bodies: The Human Figure in English Culture c. 1540–1660Reaktion Books, 1990, ISBN 0-948462-08-6

- Hearn, Karen, ed. Dynasties: Painting in Tudor and Jacobean England 1530–1630. New York: Rizzoli, 1995. ISBN 0-8478-1940-Ten (Hearn 1995)

- Hearn, Karen: Marcus Gheeraerts 2 Elizabeth Artist, London: Tate Publishing 2002, ISBN ane-85437-443-5 (Hearn 2002)

- Kinney, Arthur F.: Nicholas Hilliard's "Art of Limning", Northeastern Academy Press, 1983, ISBN 0-930350-31-vi

- Levey, Michael, Painting at Court, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1971

- Penny, Nicholas, National Gallery Catalogues (new series): The Sixteenth Century Italian Paintings, Volume 1, 2004, National Gallery Publications Ltd, ISBN 1-85709-908-vii

- Museo del Prado, Catálogo de las pinturas, 1996, Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, Madrid, ISBN 84-87317-53-seven (Prado)

- Reynolds, Graham: Nicholas Hilliard & Isaac Oliver, Her Majesty's Stationery Role, 1971

- Stiff, Roy: The English Icon: Elizabethan and Jacobean Portraiture, 1969, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London (Potent 1969)

- Strong, Roy: Nicholas Hilliard, 1975, Michael Joseph Ltd, London, ISBN 0-7181-1301-two (Potent 1975)

- Strong, Roy: The Cult of Elizabeth, 1977, Thames and Hudson, London, ISBN 0-500-23263-6 (Strong 1977)

- Strong, Roy: Artists of the Tudor Court: The Portrait Miniature Rediscovered 1520–1620, Victoria & Albert Museum exhibit catalogue, 1983, ISBN 0-905209-34-half-dozen (Strong 1983)

- Potent, Roy: Art and Power; Renaissance Festivals 1450–1650, 1984, The Boydell Press;ISBN 0-85115-200-vii (Strong 1984)

- Potent, Roy: "From Manuscript to Miniature" in John Murdoch, Jim Murrell, Patrick J. Noon & Roy Stiff, The English Miniature, Yale Academy Press, New Oasis and London, 1981 (Strong 1981)

- Strong, Roy: Gloriana: The Portraits of Queen Elizabeth I, Thames and Hudson, 1987, ISBN 0-500-25098-seven (Strong 1987)

- Potent, Roy: The Spirit of Britain, 1999, Hutchison, London, ISBN 1-85681-534-10 (Stiff 1999)

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh; Princes and Artists, Patronage and Ideology at 4 Habsburg Courts 1517–1633, Thames & Hudson, London, 1976, ISBN 0-500-23232-6

- Waterhouse, Ellis; Painting in Britain, 1530–1790, 4th Edn, 1978, Penguin Books (now Yale History of Fine art series)

- Yates, Frances: Astraea: The Imperial Theme in the Sixteenth Century, London and Boston: Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1975, ISBN 0-7100-7971-0

Further reading [edit]

- Connolly, Annaliese, and Hopkins, Lisa (eds.), Goddesses and Queens: The Iconography of Elizabeth, 2007, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0719076770

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portraiture_of_Elizabeth_I

0 Response to "Art in the Elizabethan Era Portraits in a Frame in the Elizabethan Era"

Post a Comment